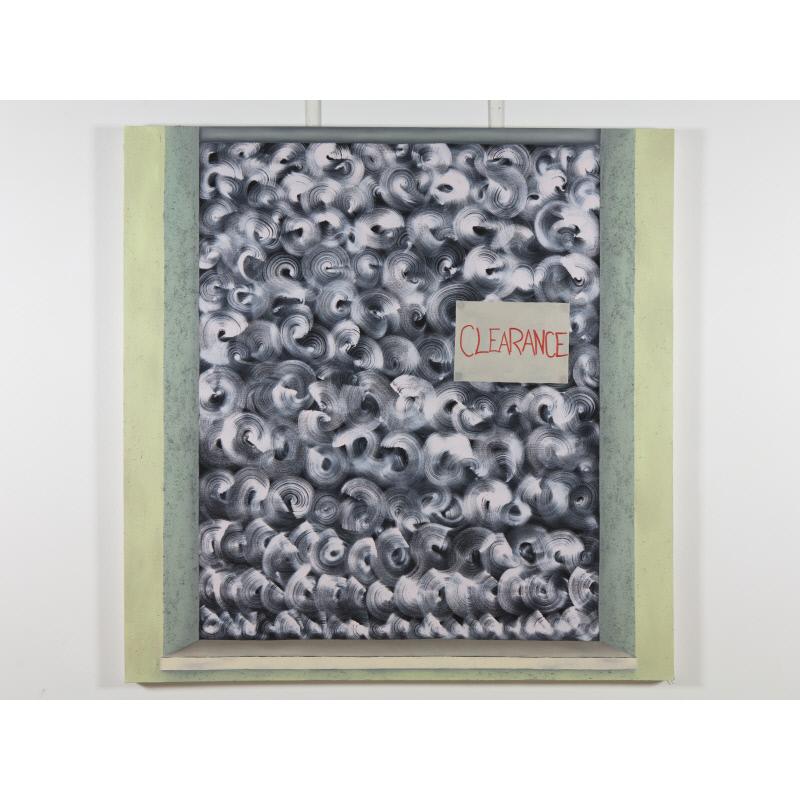

Dose

Collection:UAL Art Collection

Date: 2019

Artist: Molly McFadden (Northern Irish)

Dimensions:

145 x 143 x 10cm

Medium: Oil and sawdust on canvas

Object number: UAC 1004

DescriptionMolly studied BA Fine Art: Painting at Wimbledon College of Arts. She says:

'My work is an indirect look at and an exploration of the effects of The Troubles on Derry City. I make paintings that are less immediately concerned with the violence of the past, but instead intend to reflect the environment of the city, by depicting the mundane spaces the citizens inhabit and the silent objects we ritualistically interact with.

The act painting of these unlikely subjects gives weight to their banal familiarity, which, in turn augments nuances of the dreary existential reality in which the North finds itself. These objects appear as the passive participants of a lingering trauma, as victims of the poisoned land, as quiet reflections of the bleak realities of our society. Through their readings, they become the yardstick by which we measure the deep-seated issues, such as sectarianism, suicide and division that continue to define the narrative of the nation.

In order to avoid making work that could appear to sensationalize such subjects, I tend to be more oblique in my responses to them. Taking cues from Northern Irish poets, such as Seamus Heaney and John Montague, I use layered emblem and metaphor to describe the post-conflict climate of the North. As well as this lending itself to a more accurate representation of the psychic landscape of the North, in its culture of silence and its own tendency toward coded symbolism, the paintings also allow the viewer a less confrontational way into these difficult and charged subjects.'

'My work is an indirect look at and an exploration of the effects of The Troubles on Derry City. I make paintings that are less immediately concerned with the violence of the past, but instead intend to reflect the environment of the city, by depicting the mundane spaces the citizens inhabit and the silent objects we ritualistically interact with.

The act painting of these unlikely subjects gives weight to their banal familiarity, which, in turn augments nuances of the dreary existential reality in which the North finds itself. These objects appear as the passive participants of a lingering trauma, as victims of the poisoned land, as quiet reflections of the bleak realities of our society. Through their readings, they become the yardstick by which we measure the deep-seated issues, such as sectarianism, suicide and division that continue to define the narrative of the nation.

In order to avoid making work that could appear to sensationalize such subjects, I tend to be more oblique in my responses to them. Taking cues from Northern Irish poets, such as Seamus Heaney and John Montague, I use layered emblem and metaphor to describe the post-conflict climate of the North. As well as this lending itself to a more accurate representation of the psychic landscape of the North, in its culture of silence and its own tendency toward coded symbolism, the paintings also allow the viewer a less confrontational way into these difficult and charged subjects.'